|

Phuket's Old Town Movement

Text & photographs by Khoo Salma Nasution

Asian Public Intellectual (API) Fellow, Nippon Foundation

History History

Phuket, 'pearl of the Andaman' is more than a beach resort. It has a rich history as tin-mining country peopled by Siamese, Chinese, Malays, Indians, Eurasians and sea gypsies. A unique community in Phuket are the 'Baba', with its own way of life, language, dress and food. The core of this community was formed by early unions between Hokkien tin-miners and Siamese women. This distinctive Baba heritage can be seen in old Phuket town.

Since the 16th century, the Europeans have been interested in the tin trade of Phuket. The called the island 'Junk Ceylon' (Ujong Thalang). The Burmese invasion of 1809 devastated the old settlement of Thalang, sparking an exodus of the original inhabitants. From the 1820s onwards, mining in Phuket was in the hands of Chinese adventurers from the British Straits Settlements, particularly Penang. During this period, fossicking spread from the interior at Kathu to the bay of Tongkah, and around 1850, the town of 'Tongkah' was formed. This settlement forms the historic core of Phuket town today.

Early Phuket town was linked by a few roads and a network of canals and waterways leading to Tongkah Bay. Coastal vessels transported tin from Phuket to Penang, and returned with foodstuffs and hardware. In the past, workers flocked to town to sell their ore, to stock up on provisions, and to remit money. In order to forget their hardship and homesickness, they indulged in the four pleasures - wine, women, opium and gambling. Thalang Road was the main street where the big traders had their shops. Soi Romanee was the red light district. Early Phuket town was linked by a few roads and a network of canals and waterways leading to Tongkah Bay. Coastal vessels transported tin from Phuket to Penang, and returned with foodstuffs and hardware. In the past, workers flocked to town to sell their ore, to stock up on provisions, and to remit money. In order to forget their hardship and homesickness, they indulged in the four pleasures - wine, women, opium and gambling. Thalang Road was the main street where the big traders had their shops. Soi Romanee was the red light district.

In the early 20th century, a measure of civilization was brought by Phraya Rassada Nupradit (Khaw Sim Bee na Ranong) during his term as High Commissioner of greater Phuket (1900-1913). He gave a large concession to an Australian-European mining company, Tongkah Harbour Dredging, in return for funds to develop the public infrastructure. Roads were built, canals were de-silted, and a number of public buildings were put up. With Phuket becoming safer, more traders and their families, especially those from Penang, settled down in Phuket. With greater prosperity, more schools and temples were endowed.

Tin from the frontier settlement of Phuket was smelted and exported at Penang, the nearest major seaport, Penang. Sea travel to Penang was faster and safer than land travel to Bangkok. Once communications were improved, Phuket gradaully changed its orientation towards Bangkok, especially after the Second World War. But by that time, Phuket had developed its distinctive local character.

With the inauguration of direct flights between Europe and Bangkok in the early 1970s, Phuket started to become a tourist destination. Ten years later, the tin market collapsed but fortunately the economy was rescued by the growth of tourism. Many former tin mines were converted into luxury resorts. The old town, on the other hand, has been largely bypassed by the tourism industry until recently.

Architectural Heritage

The cultural built heritage of Phuket is a reflection of the settlement's prosperity during the tin boom days. The townscape is unique in Thailand, but resembles that of the British Striats Settlements, which comprised, Penang, Malacca and Singapore. The architecture is usually called 'Sino-Portuguese' by the Bangkok architects today. However, any Portuguese influence would have been rather indirect, via Malacca's historic influence on Straits Settlements architecture. Although Phuket had early contacts with the Portuguese, most evidence of European settlement was destroyed during the Burmese invasion. The cultural built heritage of Phuket is a reflection of the settlement's prosperity during the tin boom days. The townscape is unique in Thailand, but resembles that of the British Striats Settlements, which comprised, Penang, Malacca and Singapore. The architecture is usually called 'Sino-Portuguese' by the Bangkok architects today. However, any Portuguese influence would have been rather indirect, via Malacca's historic influence on Straits Settlements architecture. Although Phuket had early contacts with the Portuguese, most evidence of European settlement was destroyed during the Burmese invasion.

Phuket town was really modelled after British colonial Penang, and that was the origin of any European influence on its architecture. Upon close examination, it is evident that Phuket's shophouses and villas resemble those in Penang in form, materials and design, although the occasional Thai motif reminds us that we are in Thailand. Phuket oral tradition in several cases claim that Penang architects, builders and materials were brought to Phuket for its best mansions. We are waiting for old building plans to be revealed to prove that this was indeed so. Thai architects entered the scene no later than 1930, and from then on, Phuket architecture began to diverge from Penang style. Phuket town was really modelled after British colonial Penang, and that was the origin of any European influence on its architecture. Upon close examination, it is evident that Phuket's shophouses and villas resemble those in Penang in form, materials and design, although the occasional Thai motif reminds us that we are in Thailand. Phuket oral tradition in several cases claim that Penang architects, builders and materials were brought to Phuket for its best mansions. We are waiting for old building plans to be revealed to prove that this was indeed so. Thai architects entered the scene no later than 1930, and from then on, Phuket architecture began to diverge from Penang style.

In 1993, the Siamese Architects Association recognized this historic area with a conservation award given collectively to 'Shop and houses of Phuket city centre (Ancient Rowhouses)' on Thalang, Krabi, Dibuk, Phangnga, Rasada, Ranong, Yaowarat and Phuket Roads. These eight roads, plus two lanes, namely Soi Romanee and Soi Sun Uthit, form the pre-Second World War town.

Phuket town has modernised with the rest of the island. In the historic centre, the narrow streets have to accommodate motorised traffic, while the five-footways are impenetrable in some parts. The streetscapes are largely intact, though broken up in some places by blockish modern infill and oversized plastic signage. On the whole, the character of old Phuket town is distinctive and charming enough to attract both Thai and foreign visitors. Phuket town has modernised with the rest of the island. In the historic centre, the narrow streets have to accommodate motorised traffic, while the five-footways are impenetrable in some parts. The streetscapes are largely intact, though broken up in some places by blockish modern infill and oversized plastic signage. On the whole, the character of old Phuket town is distinctive and charming enough to attract both Thai and foreign visitors.

Though the old town is no longer the commercial hub of Phuket, most of the shophouses are still functioning as shops and residences. Eating places abound in Phuket and the old town is no exception. The main street, Thalang Road is still known for certain trades, especially batik textiles. While the older businesses tend to be provisioners, wholesalers, tin dealers, hardware shops and machinery suppliers, today there is a slow but sure gentrification as antique shops, cafes and European restaurants are making their appearance.

The Phuket Shophouse

The dominant urban form in the old town is the 'shophouse', (from the Hokkien word tiam choo, literally, shop + house). Part of a row of houses, each unit has a narrow frontage on a long plot. The side elevation can be described as several pitched roof sections, alternating with internal courtyards (chhim chneh). These internal courtyards, which let air and light into the long, narrow houses, are the focus for lovely atrium spaces. Quite a few Phuket shophouses still have their original water wells. The dominant urban form in the old town is the 'shophouse', (from the Hokkien word tiam choo, literally, shop + house). Part of a row of houses, each unit has a narrow frontage on a long plot. The side elevation can be described as several pitched roof sections, alternating with internal courtyards (chhim chneh). These internal courtyards, which let air and light into the long, narrow houses, are the focus for lovely atrium spaces. Quite a few Phuket shophouses still have their original water wells.

If the front portion is used as a shop, the ground facade is usually open to the street, while the rest of the house could be used as a residence or storage area. The more affluent families use the whole 'shophouse' as a residence. In this case, the house would have an elegant facade concealing a private living space with ornate screens and indoor gardens. The upper part of the facade is often articulated with windows in three bays, surrounded by fancy stucco decoration. Fine examples of this can be seen along Dibuk Road.

Whether residential or commercial, the shophouses are linked by a continuous front arcade known as a 'five-footway', which offer shade, shelter and safety to pedestrians. The old town consists of a gridiron of streets, each flanked by double-storey shophouse rows, producing a dense living pattern. With criss-crossing lines of sight, this close-knit neighbourhood produced a high level of public safety and community networking.

A dozen or so villas survive in the core area, a few with their gardens intact, others with compounds encroached by smaller buildings. Of these, the most attractive and accessible is the Pithak Chinpracha house, maintained by a sprightly 76 year old owner, Khun Pracha. The house is offered in the commercial cultural tours of Phuket. Khun Pracha believes in the 'uniqueness of Phuket' and started showing 98 Krabi Road to visitors years ago, before most Phuket people had even heard of the word 'heritage'. A dozen or so villas survive in the core area, a few with their gardens intact, others with compounds encroached by smaller buildings. Of these, the most attractive and accessible is the Pithak Chinpracha house, maintained by a sprightly 76 year old owner, Khun Pracha. The house is offered in the commercial cultural tours of Phuket. Khun Pracha believes in the 'uniqueness of Phuket' and started showing 98 Krabi Road to visitors years ago, before most Phuket people had even heard of the word 'heritage'.

Urban Conservation

In the last two decades, development agencies, academia and City Hall have slowly but surely set the stage for the revitalization of the old town. The old town has been declared 'conservation of cultural heritage zone' by the Office of Environmental Policy and Planning (OEPP), of the National Environment Board. In the Development Plan of Muang Phuket Municipality Area published in 2004, the designated conservation area is 19 rai (about 0.5 square kilometres) with a built-up area of 31,069 sq metres.

Development guidelines specify a 12-metre height limit in order to maintain the 2-3 storey building scale of the shophouse neighbourhood. New infill buildings conforming to architectural prescriptions are no longer required to set back for road-widening. Guidelines are disseminated for appropriate signage. Traditional activities which reflect Phuket's identity are encouraged. Physical restoration is promoted, but as yet no financial incentives are available.

From the 1980s, Phuket has been developing and modernising its local authority with the support of GTZ's 'Urban Environmental Management at Local Level Project'. The Municipality has prepared a budget allocation for the conservation of the old town since 1994. Local authorities were strengthened when the government was restructured and decentralised following the financial crisis in Thailand in 1997.

The conservation of old Phuket has been furthered through collaborations between the Municipality, the academia and local leaders. A special impetus has been provided since 1997 by the work of architecture lecturer Dr. Yongthanit Pimonsathean and his students from Bangkok. With the full support of the City Hall, Dr. Yongthanit's university team has developed an architectural database, identifying heritage buildings, measuring and drawing them up. They have also assisted the municipality in conducting surveys, providing advice to house owners and sourcing appropriate materials and craftsmen.

The Municipality and university team jointly organised exhibitions and facilitated community forums about the future of the old town. A few house owners volunteered or were persuaded to remove the obstructions to the five-footway sections in front of their houses. In celebration of this cooperation between the Municipality and residents, the first Old Phuket Town Festival was organised in 1998. This event has been repeated annually since, with allocations from the Phuket government. The festival showcases the Baba lifestyle, food, costumes, performing arts and architectural heritage.

During the Old Phuket Town Festival, Thalang Road has was closed off to cars and converted into a 'walking street', bringing back the ambience when the old town bustled with pedestrians instead of cars. An important exhibition and community meeting venue is the hall of Thai Wah School, the oldest Chinese school in Thailand, conveniently located at one end of the main street, on Krabi Road. As the school has moved out to new premises in the town outskirts, Thai Wah's Alumni Association now wants to convert their 1934 'Sino-Portuguese' building into a museum for Phuket Baba culture. During the Old Phuket Town Festival, Thalang Road has was closed off to cars and converted into a 'walking street', bringing back the ambience when the old town bustled with pedestrians instead of cars. An important exhibition and community meeting venue is the hall of Thai Wah School, the oldest Chinese school in Thailand, conveniently located at one end of the main street, on Krabi Road. As the school has moved out to new premises in the town outskirts, Thai Wah's Alumni Association now wants to convert their 1934 'Sino-Portuguese' building into a museum for Phuket Baba culture.

Between 1998 and 2002, the Municipality awarded more than 60 certificates of conservation effort to house owners who have restored or maintained their houses. This scheme speeded up the process of building local awareness and pride. In addition, it helped ordinary people to differentiate between what was good conservation practice and what was not.

New approaches to conservation have been explored. A motorcycle business had its new showroom, at the corner of Thalang and Phuket Roads, designed and built in sympathetic scale and design. Two very recent examples are worth mentioning. A 1950s shophouse has been adaptively reused with tasteful interior design employing traditional materials. A historic shophouse has been conserved and exquisitely interpreted as a cafe and gallery.

Phuket old town now faces the some of the same conservation issues as George Town as its unofficial 'sister city', Penang. However, there are important differences. The historic core of Phuket is perhaps one-fifth the size of that in Penang. Most of the old shophouses in Penang were mainly tenanted under the Rent Control Act, and the rift between the aspirations of owners and tenants worked against the objectives of conservation. In contrast, the majority of the old shophouses in Phuket owner-occupied, hence generally better cared for, even though the number which are sadly falling into decay is not negligible.

Old Phuket Foundation

The special qualities of old Phuket town have created an extraordinary sense of belonging for those who grew up there. This is the impression I get from talking to a number of sons and daughters of Thalang Road-Krabi Road, who in mid-2005 are now leading members of the Phuket community. Collectively, they represent a phenomenon which could be called the 'old town movement'. This flame burns brightly during the annual Old Phuket Town Festival. The movement has several dimensions, including that of cultural identity, but for the purpose of this article, we will focus on the urban strategies pursued in the physical conservation and economic revitalization of the site. The special qualities of old Phuket town have created an extraordinary sense of belonging for those who grew up there. This is the impression I get from talking to a number of sons and daughters of Thalang Road-Krabi Road, who in mid-2005 are now leading members of the Phuket community. Collectively, they represent a phenomenon which could be called the 'old town movement'. This flame burns brightly during the annual Old Phuket Town Festival. The movement has several dimensions, including that of cultural identity, but for the purpose of this article, we will focus on the urban strategies pursued in the physical conservation and economic revitalization of the site.

After the tsunami of December 2004, many Phuket people had to rethink the way Phuket has developed. As the economy has temporarily slowed down, many busy local leaders finally have the time to turn their attention to something close to their heart - the revitalization of old Phuket.

In 2003, the Old Phuket Foundation was established to spearhead initiatives that could be jointly supported by government, business sector and community. The City Hall appointed a committee of 15 civic leaders, each serving a four-year term. Its objectives are to revive, restore and conserve the Phuket way of life, arts, architecture and heritage; to raise awareness among Phuket people about the importance of the old town, and to promote Phuket's cultural life.

The Old Phuket Foundation chose the five-footway as its symbol. It represents the old town, safety, access, and the middle ground between the private and the public. For the same reasons, the recovery of the five-footway as public space has great symbolic value for all those involved in the old town revitalization. Currently, the street is streamlined to one-way traffic and parking is allowed on right and left sides of the street on alternate days of the week, while pedestrians walk on a narrow but nicely made pavement covering the old drains.

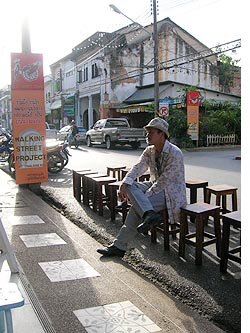

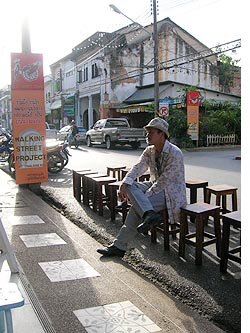

The City Hall, in collaboration with the Foundation, plans to turn Thalang Road, with its 141 units of shophouses, and the smaller Soi Romanee, into a permanent 'walking street' or pedestrianised zone, and to generally improve the street infrastructure. The main objective is the revitalization of Thalang Road, and as such, the authorities and stakeholders alike recognize that pedestrianisation must work for and not against economic vitality. By starting with the Old Phuket Town Festival and graduating to the weekend bazaar, it is hoped that these experiments of closing of the street to traffic will prove economically and not just aesthetically successful.

In preparation for this pedestrianisation scheme, the City has already converted an adjacent city block into a green city park and car park. A weekend bazaar is in the pipeline for the later part of 2005 as part of the 'Walking Street' project. The leaders of the Old Phuket Foundation have held public talks and also gone down to the ground, by conducting a house-to-house survey along Thalang Road. In preparation for this pedestrianisation scheme, the City has already converted an adjacent city block into a green city park and car park. A weekend bazaar is in the pipeline for the later part of 2005 as part of the 'Walking Street' project. The leaders of the Old Phuket Foundation have held public talks and also gone down to the ground, by conducting a house-to-house survey along Thalang Road.

The intention of the 'Walking Street' programme is to recreate a festive atmosphere in the street, showcasing traditional Baba lifestyle, dress, food as well as crafts and performing arts. The national government is also sponsoring cultural activities to coincide with the street bazaar, with funds specially allocated to boost to Phuket's recovering tourism sector.

As part of the revitalization campaign, Thalang Road will be portrayed to tourists as the 'real Phuket'. To the government, the old town is mainly another selling point for Phuket tourism, whereas the shopkeepers hope that the weekend bazaar will be good for business. But those who grew up on Thalang Road dream of bringing back the human bustle and the primacy of the main street. Whatever the individual motivations, community ownership of the 'Walking Street' project will be essential to its success, and the Old Phuket Town Foundation has a key role to play in making this a reality.

About the writer: Khoo Salma Nasution is a Penang-based author. She conducted research in Phuket as a Nippon Foundation Asian Public Intellectual (API) fellow in May to September 2005.

.

|

Heritage of

Phuket Town

Click here

* * *

Architecture

Click here

* * *

Streetscape

Click here

* * *

Thalang Road

Click here

* * *

China Inn

Click here

* * *

Pithak Chinpracha

House Museum

Click here

* * *

Phuket Thai Hua

School Museum

Click here

* * *

Art in the City

Click here

* * *

.

The Halal Festival In Kamala

Click here for full story

.

Remembering Princess Mahsuri

Click here for full story of the tragic princess from Phuket, and her descendants

|

Early Phuket town was linked by a few roads and a network of canals and waterways leading to Tongkah Bay. Coastal vessels transported tin from Phuket to Penang, and returned with foodstuffs and hardware. In the past, workers flocked to town to sell their ore, to stock up on provisions, and to remit money. In order to forget their hardship and homesickness, they indulged in the four pleasures - wine, women, opium and gambling. Thalang Road was the main street where the big traders had their shops. Soi Romanee was the red light district.

Early Phuket town was linked by a few roads and a network of canals and waterways leading to Tongkah Bay. Coastal vessels transported tin from Phuket to Penang, and returned with foodstuffs and hardware. In the past, workers flocked to town to sell their ore, to stock up on provisions, and to remit money. In order to forget their hardship and homesickness, they indulged in the four pleasures - wine, women, opium and gambling. Thalang Road was the main street where the big traders had their shops. Soi Romanee was the red light district. The cultural built heritage of Phuket is a reflection of the settlement's prosperity during the tin boom days. The townscape is unique in Thailand, but resembles that of the British Striats Settlements, which comprised, Penang, Malacca and Singapore. The architecture is usually called 'Sino-Portuguese' by the Bangkok architects today. However, any Portuguese influence would have been rather indirect, via Malacca's historic influence on Straits Settlements architecture. Although Phuket had early contacts with the Portuguese, most evidence of European settlement was destroyed during the Burmese invasion.

The cultural built heritage of Phuket is a reflection of the settlement's prosperity during the tin boom days. The townscape is unique in Thailand, but resembles that of the British Striats Settlements, which comprised, Penang, Malacca and Singapore. The architecture is usually called 'Sino-Portuguese' by the Bangkok architects today. However, any Portuguese influence would have been rather indirect, via Malacca's historic influence on Straits Settlements architecture. Although Phuket had early contacts with the Portuguese, most evidence of European settlement was destroyed during the Burmese invasion. Phuket town was really modelled after British colonial Penang, and that was the origin of any European influence on its architecture. Upon close examination, it is evident that Phuket's shophouses and villas resemble those in Penang in form, materials and design, although the occasional Thai motif reminds us that we are in Thailand. Phuket oral tradition in several cases claim that Penang architects, builders and materials were brought to Phuket for its best mansions. We are waiting for old building plans to be revealed to prove that this was indeed so. Thai architects entered the scene no later than 1930, and from then on, Phuket architecture began to diverge from Penang style.

Phuket town was really modelled after British colonial Penang, and that was the origin of any European influence on its architecture. Upon close examination, it is evident that Phuket's shophouses and villas resemble those in Penang in form, materials and design, although the occasional Thai motif reminds us that we are in Thailand. Phuket oral tradition in several cases claim that Penang architects, builders and materials were brought to Phuket for its best mansions. We are waiting for old building plans to be revealed to prove that this was indeed so. Thai architects entered the scene no later than 1930, and from then on, Phuket architecture began to diverge from Penang style. Phuket town has modernised with the rest of the island. In the historic centre, the narrow streets have to accommodate motorised traffic, while the five-footways are impenetrable in some parts. The streetscapes are largely intact, though broken up in some places by blockish modern infill and oversized plastic signage. On the whole, the character of old Phuket town is distinctive and charming enough to attract both Thai and foreign visitors.

Phuket town has modernised with the rest of the island. In the historic centre, the narrow streets have to accommodate motorised traffic, while the five-footways are impenetrable in some parts. The streetscapes are largely intact, though broken up in some places by blockish modern infill and oversized plastic signage. On the whole, the character of old Phuket town is distinctive and charming enough to attract both Thai and foreign visitors. The dominant urban form in the old town is the 'shophouse', (from the Hokkien word tiam choo, literally, shop + house). Part of a row of houses, each unit has a narrow frontage on a long plot. The side elevation can be described as several pitched roof sections, alternating with internal courtyards (chhim chneh). These internal courtyards, which let air and light into the long, narrow houses, are the focus for lovely atrium spaces. Quite a few Phuket shophouses still have their original water wells.

The dominant urban form in the old town is the 'shophouse', (from the Hokkien word tiam choo, literally, shop + house). Part of a row of houses, each unit has a narrow frontage on a long plot. The side elevation can be described as several pitched roof sections, alternating with internal courtyards (chhim chneh). These internal courtyards, which let air and light into the long, narrow houses, are the focus for lovely atrium spaces. Quite a few Phuket shophouses still have their original water wells. A dozen or so villas survive in the core area, a few with their gardens intact, others with compounds encroached by smaller buildings. Of these, the most attractive and accessible is the Pithak Chinpracha house, maintained by a sprightly 76 year old owner, Khun Pracha. The house is offered in the commercial cultural tours of Phuket. Khun Pracha believes in the 'uniqueness of Phuket' and started showing 98 Krabi Road to visitors years ago, before most Phuket people had even heard of the word 'heritage'.

A dozen or so villas survive in the core area, a few with their gardens intact, others with compounds encroached by smaller buildings. Of these, the most attractive and accessible is the Pithak Chinpracha house, maintained by a sprightly 76 year old owner, Khun Pracha. The house is offered in the commercial cultural tours of Phuket. Khun Pracha believes in the 'uniqueness of Phuket' and started showing 98 Krabi Road to visitors years ago, before most Phuket people had even heard of the word 'heritage'. During the Old Phuket Town Festival, Thalang Road has was closed off to cars and converted into a 'walking street', bringing back the ambience when the old town bustled with pedestrians instead of cars. An important exhibition and community meeting venue is the hall of Thai Wah School, the oldest Chinese school in Thailand, conveniently located at one end of the main street, on Krabi Road. As the school has moved out to new premises in the town outskirts, Thai Wah's Alumni Association now wants to convert their 1934 'Sino-Portuguese' building into a museum for Phuket Baba culture.

During the Old Phuket Town Festival, Thalang Road has was closed off to cars and converted into a 'walking street', bringing back the ambience when the old town bustled with pedestrians instead of cars. An important exhibition and community meeting venue is the hall of Thai Wah School, the oldest Chinese school in Thailand, conveniently located at one end of the main street, on Krabi Road. As the school has moved out to new premises in the town outskirts, Thai Wah's Alumni Association now wants to convert their 1934 'Sino-Portuguese' building into a museum for Phuket Baba culture. The special qualities of old Phuket town have created an extraordinary sense of belonging for those who grew up there. This is the impression I get from talking to a number of sons and daughters of Thalang Road-Krabi Road, who in mid-2005 are now leading members of the Phuket community. Collectively, they represent a phenomenon which could be called the 'old town movement'. This flame burns brightly during the annual Old Phuket Town Festival. The movement has several dimensions, including that of cultural identity, but for the purpose of this article, we will focus on the urban strategies pursued in the physical conservation and economic revitalization of the site.

The special qualities of old Phuket town have created an extraordinary sense of belonging for those who grew up there. This is the impression I get from talking to a number of sons and daughters of Thalang Road-Krabi Road, who in mid-2005 are now leading members of the Phuket community. Collectively, they represent a phenomenon which could be called the 'old town movement'. This flame burns brightly during the annual Old Phuket Town Festival. The movement has several dimensions, including that of cultural identity, but for the purpose of this article, we will focus on the urban strategies pursued in the physical conservation and economic revitalization of the site. In preparation for this pedestrianisation scheme, the City has already converted an adjacent city block into a green city park and car park. A weekend bazaar is in the pipeline for the later part of 2005 as part of the 'Walking Street' project. The leaders of the Old Phuket Foundation have held public talks and also gone down to the ground, by conducting a house-to-house survey along Thalang Road.

In preparation for this pedestrianisation scheme, the City has already converted an adjacent city block into a green city park and car park. A weekend bazaar is in the pipeline for the later part of 2005 as part of the 'Walking Street' project. The leaders of the Old Phuket Foundation have held public talks and also gone down to the ground, by conducting a house-to-house survey along Thalang Road.